History of the Smiley

https://www.frieze.com/article/brief-history-smiley

Strangely the roots of the smiley face are in the capitalist and corporate world. Originating in Worcester, Massachusetts in 1963 when graphic designer Harvey Ball design the cheery smile for State Mutual Life Assurance Company as a morale booster for employees. The smiley was never copywritten and it soon became a ‘feel good ‘ symbol in the 1960s in line with the culture of freedom and hedonism which emerged through the hippy movement and summer of love.

“The simple yellow smiley face created in 1963 (probably) has led to tens of thousands of variations and has appeared on everything from pillows and posters to perfume and pop art. Its meaning has changed with social and cultural values: from the optimistic message of a 1960s insurance company, to commercialized logo, to an ironic fashion statement, to a symbol of rave culture imprinted on ecstasy pills, to a wordless expression of emotions in text messages. In the groundbreaking comic Watchmen, a blood-stained smiley face motif serves as something of a critique of American politics in a dystopian world featuring depressed and traumatized superheroes. Perhaps Watchmanartist Dave Gibbons best explains the mystique of the smiley: “It’s just a yellow field with three marks on it. It couldn’t be more simple. And so to that degree, it’s empty. It’s ready for meaning. If you put it in a nursery setting…It fits in well. If you take it and put it on a riot policeman’s gas mask, then it becomes something completely different.” – https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/who-really-invented-the-smiley-face-2058483/

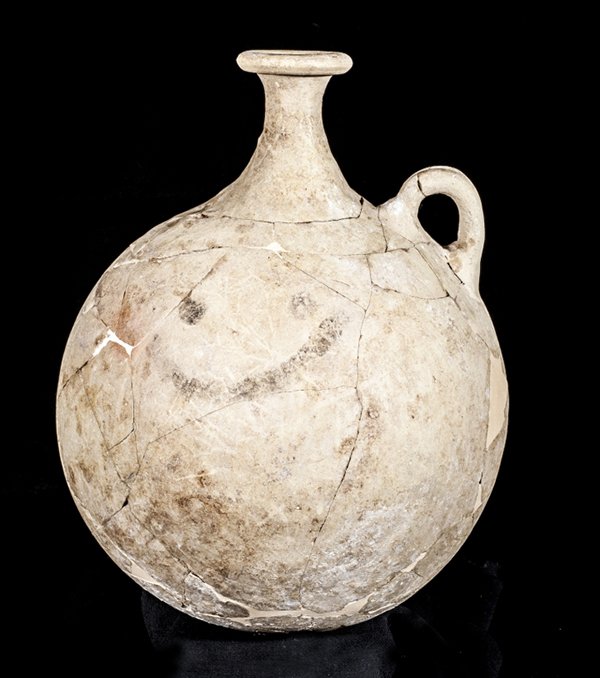

In 2017 an artefact dating to 1,700 BCE was discovered in Turkey and appear to have a smiley emoji! Its a drinking vessel believed to have been for ‘sweet drink’ sherbet!

Casting a Bronze Smiley

The iconic smiley face of acid house has been reproduced and represented across a multitude of physical forms; it adorns artefacts such as clothing, household items, art prints, and other decorative objects. These items harbour a nostalgia for the rave era but do not give an understanding of Rave or the culture associated with the free party scene, the connection is merely through a visual aesthetic.

Many smiley objects exist and continue to be produced today; they are the archeology of our present but begs the question, what traces will be left and how ‘out of context’ will these items be described in the future? Our present day archives will be interpreted by a future society through the context in which they live, and we can not predict which elements may become incorporated into a narrative that leads to misinterpretation of the significance of these artefacts, as is the case with present day archaeologists and the artefacts left by ancient civilisations.

We can consider, what is the purpose of the creation of a bronze smiley? Perhaps it is an art object, though its materiality of a semi precious metal such as bronze may lead to its interpretation as an icon to represent a deity of Rave. If similar smiley faces were discovered in a multitude of places, would they constitute and archeological culture and thus an assemblage?